I. Introduction

Purpose: This report provides an in-depth comparative analysis of the provisions governing the protection of trademarks as stipulated in the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), finalized in 1995 as part of the Marrakesh Agreement establishing the World Trade Organization (WTO), and their subsequent implementation and compliance within India’s domestic legislation, specifically the Trade Marks Act, 1999. The analysis aims to elucidate the relationship between the international minimum standards set by TRIPS and the national framework established by India. 1

Context: The TRIPS Agreement stands as a landmark international legal instrument, integrating intellectual property law into the multilateral trading system for the first time and establishing comprehensive minimum standards for the regulation and enforcement of various forms of intellectual property, including trademarks, among WTO member nations.3 As a signatory to the WTO Agreement, India undertook the obligation to align its national intellectual property laws with these minimum standards.10 Consequently, the Indian Parliament enacted the Trade Marks Act, 1999, repealing and replacing the earlier Trade and Merchandise Marks Act, 1958. The explicit objective of the 1999 Act was to amend and consolidate the law relating to trademarks in India, providing for the registration and enhanced protection of trademarks for both goods and services, and preventing the use of fraudulent marks, thereby harmonizing Indian law with its international commitments under TRIPS.13

The enactment of the Trade Marks Act, 1999, therefore, represents more than a mere update of domestic legislation. It signifies a crucial step in India’s post-1991 economic liberalization and integration into the global trading architecture facilitated by the WTO.12 Adherence to harmonized intellectual property standards, as mandated by TRIPS, became an essential component of participation in this system, understood as necessary for facilitating international trade, attracting investment, and encouraging technology transfer.15 The legislative changes embodied in the 1999 Act reflect a conscious policy decision to align India’s intellectual property regime with prevailing global norms, acknowledging the linkage between robust IP protection and broader economic engagement within the multilateral framework.1

Scope Overview: This report will systematically compare key aspects of trademark law under both TRIPS and the Indian Act. The analysis will encompass: the definition and protectable subject matter of trademarks; the nature and scope of rights conferred upon registration; the term of protection and renewal provisions; permissible exceptions to trademark rights; requirements concerning the use of trademarks for acquisition and maintenance of rights; provisions governing licensing and assignment; the specific protection afforded to well-known marks; and the enforcement mechanisms mandated and implemented, including civil remedies, criminal procedures, and border measures.

II. Trademark Standards under the TRIPS Agreement (1995)

The TRIPS Agreement dedicates Section 2 of Part II (Articles 15 through 21) specifically to trademarks, establishing minimum standards that all WTO members must adhere to in their national laws.21 These standards cover protectable subject matter, rights conferred, exceptions, term of protection, use requirements, and transferability. Furthermore, the Agreement incorporates relevant provisions from the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property (1967) and mandates comprehensive enforcement measures under Part III.

A. Core Provisions (Art. 15-21)

- Article 15 (Protectable Subject Matter): TRIPS provides a broad definition, stating that “Any sign, or any combination of signs, capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings, shall be capable of constituting a trademark”.25 This includes, in particular, words (even personal names), letters, numerals, figurative elements, combinations of colours, and any combination thereof.25 Recognizing that not all signs possess inherent distinctiveness, Article 15.1 allows Members to make registrability dependent on distinctiveness acquired through use.25 Members also retain the option to require signs to be visually perceptible as a condition for registration.25

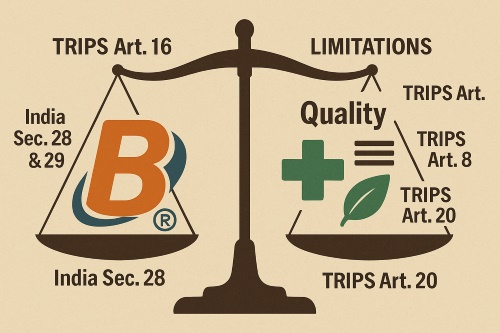

A significant procedural safeguard is established in Article 15.3: while Members may make registrability dependent on use, actual use of a trademark cannot be a condition for filing an application for registration.22 Furthermore, an application cannot be refused solely because the intended use has not commenced before the expiry of a three-year period from the application date.25 Article 15.4 explicitly prevents the nature of the goods or services from being an obstacle to registration.25 To ensure transparency and allow for challenges, Article 15.5 mandates that Members publish trademarks either before or promptly after registration and provide a reasonable opportunity for petitions to cancel the registration; the possibility of opposition procedures may also be provided.25 These provisions are supplemented by the incorporation of relevant Paris Convention articles, ensuring adherence to established international norms.6 - Article 16 (Rights Conferred): The core right granted to the owner of a registered trademark is defined in Article 16.1. It confers the exclusive right to prevent all third parties not having the owner’s consent from using in the course of trade identical or similar signs for goods or services which are identical or similar to those in respect of which the trademark is registered, where such use would result in a likelihood of confusion.25 A crucial clarification is provided: in the case of the use of an identical sign for identical goods or services, a likelihood of confusion shall be presumed.25 These rights are explicitly stated not to prejudice any existing prior rights, nor do they affect the possibility for Members to make rights available based on use.25

- Article 17 (Exceptions): Recognizing the need for balance, Article 17 permits Members to provide limited exceptions to the rights conferred by a trademark.21 An example cited is the fair use of descriptive terms.25 However, such exceptions are subject to a critical condition: they must take into account the legitimate interests of the owner of the trademark and of third parties.25 This ensures that exceptions do not unreasonably undermine the core function of the trademark.

- Article 18 (Term of Protection): TRIPS sets a minimum duration for trademark protection. The initial registration, and each subsequent renewal, must be for a term of no less than seven years.21 Importantly, the Agreement mandates that trademark registrations shall be renewable indefinitely.25

- Article 19 (Requirement of Use): If a Member requires the use of a trademark to maintain its registration, Article 19 stipulates that the registration may be cancelled only after an uninterrupted period of at least three years of non-use.21 Cancellation cannot occur if the trademark owner demonstrates valid reasons for non-use based on the existence of obstacles to such use (e.g., import restrictions or other government requirements).21 Furthermore, use of a trademark by another person under the control of the owner (such as a licensee) must be recognized as use of the trademark for the purpose of maintaining the registration.21

- Article 20 (Other Requirements): This article prohibits Members from unjustifiably encumbering the use of a trademark in the course of trade with special requirements.21 Examples of such prohibited requirements include use that must be coupled with another trademark, use in a special form, or use in a manner detrimental to the mark’s capacity to distinguish the goods or services.21 This provision aims to prevent indirect restrictions on the effective use and function of trademarks.

- Article 21 (Licensing and Assignment): Members are permitted to determine conditions on the licensing and assignment of trademarks.21 However, a key principle established is that the owner of a registered trademark shall have the right to assign the trademark with or without the transfer of the business to which the trademark belongs.21 Critically, Article 21 explicitly prohibits the compulsory licensing of trademarks.16

The formulation of these core trademark provisions within TRIPS reflects an effort to harmonize standards across diverse legal systems. Historically, common law traditions placed greater emphasis on rights derived from use and the protection of goodwill through actions like passing off, while civil law systems often prioritized rights flowing from administrative registration, sometimes irrespective of initial use.22 TRIPS navigates this divergence by setting minimum standards acceptable to both traditions. For instance, allowing registration based on intent-to-use (Art 15.3) accommodates systems where registration precedes use, while recognizing rights based on use (Art 16.1) and requiring use for maintenance (Art 19) acknowledges the common law perspective.21 Similarly, permitting assignment without goodwill (Art 21) caters to systems where the mark is viewed as property separable from the underlying business.21 By focusing on these minimum requirements and leaving implementation details flexible, TRIPS created a framework that member states could integrate into their existing legal structures, fostering convergence in outcomes without mandating identical legal mechanisms.22

B. Protection of Well-Known Marks (Art. 16.2, 16.3)

TRIPS significantly enhances the international protection available for well-known trademarks, building upon Article 6bis of the Paris Convention.

- Article 16.2 explicitly mandates that Article 6bis of the Paris Convention shall apply, mutatis mutandis, to services.25 It further requires that in determining whether a trademark is well-known, Members must consider the knowledge of the trademark in the relevant sector of the public, including knowledge within the Member state obtained as a result of the promotion of the trademark.25

- Article 16.3 introduces a substantial expansion of protection. It extends the application of Paris Article 6bis to goods or services which are not similar to those in respect of which a trademark is registered.25 This extended protection applies provided that two conditions are met: first, the use of the mark in relation to those dissimilar goods or services must indicate a connection between them and the owner of the registered trademark; and second, the interests of the owner of the registered trademark must be likely to be damaged by such use.25

This strengthening of protection for well-known marks under TRIPS, particularly the extension to dissimilar goods and services in Article 16.3, can be understood as a response to the increasing economic significance and transnational reach of brands in the latter half of the 20th century.25 As companies invested heavily in building global reputations (acknowledged by the reference to promotion in Art 16.2), the potential for unfair competition through free-riding on or dilution of famous marks, even in unrelated market segments, grew.25 The TRIPS provisions recognize that the reputational value of a well-known mark transcends specific product categories and requires broader protection against misappropriation or harm in a globalized marketplace. Article 16.3 thus represents a substantive legal development aimed at safeguarding these valuable intangible assets against evolving forms of unfair competition.25

C. Enforcement Principles (Overview of Part III, including Border Measures)

A defining feature of the TRIPS Agreement is its detailed and mandatory provisions on the enforcement of intellectual property rights, contained in Part III (Articles 41-61). These go far beyond the enforcement provisions of previous international IP conventions.

- General Obligations (Art 41): This foundational article requires Members to ensure that effective enforcement procedures are available under their national law to permit action against any act of infringement of the intellectual property rights covered by the Agreement.1 These procedures must include expeditious remedies to prevent infringements and remedies which constitute a deterrent to further infringements.21 Crucially, enforcement procedures must be fair and equitable, avoiding unnecessary complexity or cost, and avoiding unreasonable time limits or unwarranted delays.21

- Civil and Administrative Procedures (Art 42-49): This section mandates specific features for civil and administrative enforcement. Key requirements include fair and equitable procedures (Art 42), rules concerning evidence (Art 43), the availability of judicial injunctions to prevent infringement (Art 44), the awarding of damages adequate to compensate the right holder for injury suffered (Art 45), other remedies such as the disposal of infringing goods outside the channels of commerce (Art 46), the right of judicial authorities to order infringers to inform the right holder of the identity of third persons involved in the infringement (Art 47), provisions for indemnifying defendants wrongfully enjoined (Art 48), and rules governing administrative procedures where applicable (Art 49).21

- Provisional Measures (Art 50): Members must ensure their judicial authorities have the authority to order prompt and effective provisional measures.21 This includes ordering measures inaudita altera parte (without hearing the other side) where appropriate, particularly where delay is likely to cause irreparable harm or where evidence might be destroyed. These measures aim to prevent an infringement from occurring and to preserve relevant evidence.21

- Border Measures (Art 51-60): TRIPS introduces detailed requirements for border controls against counterfeit trademark goods and pirated copyright goods.21 Article 51 mandates that Members adopt procedures enabling a right holder, who has valid grounds for suspecting that the importation of such goods may take place, to lodge an application with competent authorities (administrative or judicial) for the suspension by the customs authorities of the release into free circulation of such goods.10 Subsequent articles detail the requirements for the application process (Art 52), the provision of security or equivalent assurance by the applicant (Art 53), notice of suspension to the importer and applicant (Art 54), the duration of suspension (Art 55), indemnification of the importer and owner of the goods in case of wrongful detention (Art 56), rights of inspection and information (Art 57), conditions for ex officio action by customs authorities (Art 58), remedies including forfeiture and destruction of infringing goods (Art 59), and an exemption for de minimis imports (small quantities in personal luggage or small consignments) (Art 60).21

- Criminal Procedures (Art 61): Members are required to provide for criminal procedures and penalties to be applied at least in cases of willful trademark counterfeiting or copyright piracy on a commercial scale.21 Remedies available must include imprisonment and/or monetary fines sufficiently high to provide a deterrent, consistent with the level of penalties applied for crimes of corresponding gravity.21 Authorities must also have the power to order the seizure, forfeiture, and destruction of the infringing goods and any materials and implements predominantly used in the commission of the offence.21

The inclusion of these comprehensive enforcement provisions, especially the detailed framework for border measures, marked a significant evolution in international intellectual property law. While earlier conventions like Paris and Berne primarily focused on defining substantive rights and principles like national treatment 6, TRIPS mandated the establishment of practical legal and administrative machinery for the assertion of those rights.21 By embedding these requirements within a trade agreement and specifically targeting the cross-border movement of infringing goods, TRIPS directly linked IP protection to the regulation and control of international trade.1 This framework obliges member states not merely to recognize IP rights on paper but to create functional systems capable of stopping infringing goods, thereby facilitating legitimate commerce by combating illicit trade. Consequently, TRIPS institutionalized IP enforcement as an integral component of the global trade governance system.21

III. Trademark Provisions in the Indian Trademark Act (1999)

The Trade Marks Act, 1999 (hereinafter “the Act”), represents India’s primary legislative response to its TRIPS obligations concerning trademarks. It provides a comprehensive framework for the registration, protection, and enforcement of trademarks for both goods and services.

A. Definition, Subject Matter, and Registrability (Sec 2(zb), 9, 11)

- Definition (Sec 2(zb)): The Act defines a “trade mark” as “a mark capable of being represented graphically and which is capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one person from those of others and may include shape of goods, their packaging and combination of colours…”.17 The definition further distinguishes between its application in the context of offences (Chapter XII, referring to registered marks or marks indicating a trade connection) and its broader application elsewhere in the Act (referring to marks used or proposed to be used to indicate a trade connection).33 The term “mark” itself is broadly defined in Section 2(m) to include elements such as a device, brand, heading, label, ticket, name, signature, word, letter, numeral, shape of goods, packaging, or combination of colours or any combination thereof.18

- Protectable Subject Matter: The statutory definition explicitly covers traditional marks (words, logos, names, etc.) and extends to non-traditional marks like the shape of goods, packaging, and combinations of colours.17 The Act clearly provides for the registration of service marks, a significant addition compared to the previous legislation.14 Furthermore, current practice and rules under the Act also permit the registration of sound marks and three-dimensional marks.17

- Absolute Grounds for Refusal (Sec 9): Section 9 enumerates grounds inherent to the mark itself that prevent registration.16 These include:

- Marks devoid of any distinctive character (i.e., incapable of distinguishing).

- Marks consisting exclusively of indications designating the kind, quality, quantity, intended purpose, value, geographical origin, time of production, or other characteristics of the goods/services.

- Marks consisting exclusively of indications that have become customary in the current language or bona fide trade practices.

- Marks likely to deceive the public or cause confusion.

- Marks likely to hurt the religious susceptibilities of any class or section of Indian citizens.

- Marks comprising scandalous or obscene matter.

- Marks consisting exclusively of shapes resulting from the nature of the goods, necessary for a technical result, or giving substantial value to the goods.

- Marks whose use is prohibited under the Emblems and Names (Prevention of Improper Use) Act, 1950.

- Marks otherwise disentitled to protection in a court. A crucial proviso exists: a mark shall not be refused registration under the first three grounds (lack of distinctiveness, descriptiveness, customary use) if, before the date of application, it has acquired a distinctive character through use or is a well-known trade mark.33

- Relative Grounds for Refusal (Sec 11): Section 11 deals with conflicts with earlier rights.33 Registration shall be refused if a mark, due to its identity with or similarity to an earlier trade mark and the identity or similarity of the goods or services covered, creates a likelihood of confusion on the part of the public, including the likelihood of association.33 An “earlier trade mark” is defined as a registered mark or application with an earlier date, or a trademark which, prior to the relevant date, was entitled to protection as a well-known trademark.33 The section contains detailed provisions regarding the protection and determination of well-known marks (discussed further in section III.F below). An exception is provided under Section 12 for honest concurrent use, where the Registrar may permit registration of identical or similar marks for the same or similar goods/services by more than one proprietor, subject to conditions.33

The structure adopted by the Indian Act for assessing registrability, separating absolute and relative grounds, mirrors international norms consistent with TRIPS and the Paris Convention.16 However, the explicit statutory inclusion of non-traditional marks like shapes and colours within the definition 33, along with the detailed enumeration of refusal grounds in Sections 9 and 11, provides a higher degree of legislative certainty and clarity for applicants, examiners, and courts operating within the Indian legal system, compared to relying solely on the interpretation of broader international principles.25 This detailed codification reflects a deliberate approach to implementing international standards through specific national legislation.

B. Rights, Infringement, and Exceptions (Sec 28, 29, 30, 35, 36)

- Rights Conferred (Sec 28): Subject to other provisions of the Act and any conditions entered on the register, the registration of a trade mark, if valid, grants istered.38 This includes the right to obtain relief in respect of infringement of the trade mark in the manner provided by the Act.38 This exclusive right is subject to the rights of proprietors of identical or confusingly similar trademarks that may be registered concurrently.38

- Infringement (Sec 29): Section 29 provides a detailed definition of what constitutes infringement of a registered trademark.38

- The basic definition (Sec 29(1)) involves use in the course of trade by an unauthorized person (not the proprietor or permitted user) of a mark identical with, or deceptively similar to, the registered mark in relation to the goods or services covered by the registration, in such a manner as to render the use likely to be taken as being use as a trade mark.38

- Section 29(2) clarifies that infringement occurs if the mark used is identical/similar to the registered mark, the goods/services are identical/similar, and this results in a likelihood of confusion or association.38 Section 29(3) establishes a presumption of likelihood of confusion where an identical mark is used for identical goods/services.38

- Section 29(4) specifically addresses infringement of well-known trademarks, stating that use of an identical/similar mark even on dissimilar goods/services constitutes infringement if the registered mark has a reputation in India and the use without due cause takes unfair advantage of, or is detrimental to, the distinctive character or repute of the registered mark.36

- Using a registered trademark as part of one’s trade name or business name concerning the goods/services for which the mark is registered is deemed infringement under Section 29(5).38

- Section 29(6) lists specific acts that constitute “use” for infringement purposes, including affixing the mark to goods or packaging, offering/exposing goods for sale, putting them on the market, stocking them for those purposes, offering/supplying services, importing/exporting goods under the mark, or using it on business papers or in advertising.38

- Applying the registered mark to material intended for labelling, packaging, business papers, or advertising constitutes infringement if the person knew or had reason to believe the application was unauthorized (Sec 29(7)).38

- Advertising featuring the registered mark constitutes infringement if such advertising takes unfair advantage, is contrary to honest practices in industrial/commercial matters, is detrimental to the mark’s distinctive character, or is against its reputation (Sec 29(8)).38

- Importantly, Section 29(9) clarifies that infringement can occur through the spoken use of words forming part of the registered mark, as well as by visual representation.38

- Limits/Exceptions (Sec 30): Section 30 carves out several acts that do not constitute infringement.38 These include:

- Use in accordance with honest practices in industrial or commercial matters, not taking unfair advantage or being detrimental (Sec 30(1)).

- Use indicating characteristics like kind, quality, quantity, intended purpose, value, geographical origin, etc. (Sec 30(2)(a)).

- Use indicating the intended purpose of goods (e.g., accessories or spare parts), provided it is necessary and does not create confusion about trade connection (Sec 30(2)(d)).

- Use of a mark registered subject to conditions/limitations in a manner falling outside those limitations (Sec 30(2)(b)).

- Use of a registered mark that is one of two or more registered identical or nearly resembling marks (Sec 30(2)(e)).

- Use concerning goods lawfully acquired by a person and put on the market under the registered mark by the proprietor or with their consent (Sec 30(3)).38 However, this exception does not apply if the proprietor has legitimate reasons to oppose further dealing, especially where the condition of the goods has been changed or impaired after being put on the market (Sec 30(4)).38

- Further Savings: Section 35 protects the bona fide use by a person of their own name, their place of business, or their predecessors’ names, as well as the bona fide description of the character or quality of their goods or services.38 Section 36 provides that registration does not prevent the use of a registered mark as the name or description of an article or substance, but outlines conditions under which the right to the exclusive use of such a word may cease if it becomes the common name in the trade.38

Compared to the more general standard of “likelihood of confusion” articulated in TRIPS Article 16 25, Section 29 of the Indian Act offers a significantly more detailed and expansive codification of infringing acts.38 The explicit inclusion of scenarios like use as a trade name (Sec 29(5)), specific advertising practices (Sec 29(8)), spoken use (Sec 29(9)), and the application to packaging/labels (Sec 29(7)) provides clearer statutory grounds for action in common commercial disputes. Furthermore, the language used in Section 29(4) regarding well-known marks and dissimilar goods (“takes unfair advantage of or is detrimental to the distinctive character or repute”) suggests an embrace of anti-dilution principles, potentially offering protection beyond a strict confusion analysis.38 This detailed legislative approach, while fully compliant with TRIPS, arguably provides greater clarity and potentially broader protection within the specific factual contexts addressed by the statute.

C. Term of Protection and Renewal (Sec 25)

- Term: The Act provides that the registration of a trade mark shall be for a period of ten years from the date of registration.14

- Renewal: Registration is renewable indefinitely for successive periods of ten years.18 The renewal application must be made in the prescribed manner, and the prescribed fee must be paid to the Registrar before the expiration of the current registration period (Sec 25(2)).43 The Registrar is required to send a notice to the registered proprietor before expiry, reminding them of the deadline and conditions for renewal (Sec 25(3)).43

- Grace Period and Restoration: If the renewal fee is not paid by the deadline, the Act provides a grace period of six months from the date of expiration within which the registration can still be renewed upon payment of the prescribed fee along with a surcharge (Proviso to Sec 25(3)).43 If the mark is removed from the register for non-payment, the Registrar has the power to restore the mark and renew the registration if an application is made between six months and one year from the expiration date, subject to payment of the prescribed fee and the Registrar being satisfied that it is just to do so (Sec 25(4)).43

The adoption of a ten-year term of protection and renewal represents a significant change from the seven-year term under the previous Indian law.14 This ten-year period not only exceeds the minimum seven-year term mandated by TRIPS Article 18 25 but also aligns India with the standard duration adopted by many major trademark jurisdictions worldwide. This harmonization simplifies administration, particularly for international applicants managing global trademark portfolios, and reflects a move towards adopting prevailing international norms that go beyond the TRIPS minimum requirements.43

D. Use Requirement and Non-Use Cancellation (Sec 47)

While an application can be filed based on proposed use (Sec 18(1)), maintaining a registration requires bona fide use. Section 47 provides grounds for the removal of a registered trademark from the register upon application by any aggrieved person 16:

- Grounds for Removal:

- If the mark was registered without any bona fide intention on the part of the applicant to use it in relation to the registered goods/services, and there has, in fact, been no bona fide use up to three months before the date of the cancellation application (Sec 47(1)(a)).39

- If, up to three months before the date of the cancellation application, a continuous period of five years from the date on which the trademark was actually entered in the register (or longer) had elapsed during which there was no bona fide use of the mark in relation to the registered goods/services by any proprietor (Sec 47(1)(b)).16

- Bona Fide Use: The use must be genuine commercial use, not merely token use intended to defeat cancellation provisions. Use by the proprietor or by a permitted user (including a registered user under Section 48) qualifies as use by the proprietor (Sec 48(2)).39 Use of the mark on goods exclusively for export from India also constitutes use for the purposes of the Act (Sec 56(1)).39 The tribunal may also accept the use of an associated trademark or the mark with non-substantial alterations as equivalent use (Sec 55).39

- Defence: Section 47(3) provides a defence against removal if the proprietor can show that the non-use was due to special circumstances in the trade and not due to any intention to abandon or not use the trademark.39

The five-year continuous non-use period stipulated in Section 47(1)(b) provides proprietors with a longer timeframe than the three-year minimum suggested by TRIPS Article 19 21 to establish genuine commercial use of their registered marks. This extended period acknowledges the practicalities and potential delays involved in bringing products or services to market. The specific reference point for calculating this period – the date the mark is actually entered on the register – provides a clear and unambiguous starting date.39 Furthermore, the requirement that non-use must persist up to three months before the cancellation application prevents proprietors from making defensive, last-minute token use solely to thwart a non-use challenge. These parameters reflect a considered attempt to balance the rights of trademark owners to exploit their marks with the public interest in ensuring that the trademark register does not remain cluttered with unused marks, thereby freeing up potentially valuable marks for use by others.39

E. Assignment and Licensing (Permitted Use) (Ch V, Sec 48-56)

The Act provides detailed provisions for the transfer and licensing of trademark rights.

- Assignment (Chapter V, Sec 37-45):

- The registered proprietor has the statutory power to assign the trademark (Sec 37).39

- Crucially, both registered (Sec 38) and unregistered (Sec 39) trademarks are assignable and transmissible with or without the goodwill of the business concerned.39 This aligns with the flexibility permitted under TRIPS Article 21.21

- Assignments are restricted if they would result in the creation of exclusive rights in multiple persons for identical or similar marks related to similar goods/services, likely to cause deception or confusion (Sec 40).39 Restrictions also apply to assignments that would create confusing exclusive rights in different geographical parts of India (Sec 41).39

- An assignment made without the goodwill of the business does not take effect unless the assignee applies to the Registrar within six months (extendable by up to three months) for directions regarding advertisement of the assignment, and subsequently advertises it as directed (Sec 42).39

- Associated trademarks (marks registered as associated under the Act) can only be assigned or transmitted together as a whole (Sec 44).39

- To be effective against third parties acquiring a conflicting interest without knowledge, an assignment or transmission must be registered with the Registrar by the person becoming entitled to the mark (Sec 45).39

- Licensing / Permitted Use (Sec 48-56):

- The Act defines “permitted use” as use by a person other than the registered proprietor, with the proprietor’s consent, and subject to any conditions or restrictions stipulated in a written agreement (Sec 2(1)(r)). This use can be by a formally registered user or by an unregistered licensee.

- Registered User System (Sec 48-54): The Act establishes a formal system for registering users. A person other than the proprietor can be registered as a user for some or all of the goods/services (Sec 48(1)).39 A key consequence is that permitted use by a registered user is deemed to be use by the proprietor for all purposes under the Act, including defending against non-use cancellation under Section 47 (Sec 48(2)).39

- The registration process requires a joint application by the proprietor and proposed user, accompanied by the written agreement and an affidavit detailing the relationship, the degree of control exercised by the proprietor, the goods/services, any conditions/restrictions, and the duration of permitted use (Sec 49).39

- The registration can be varied or cancelled by the Registrar upon application by the proprietor, user, or affected third parties on various grounds, including use contrary to the agreement, misrepresentation during application, changed circumstances, or non-enforcement of quality control stipulations (Sec 50).39

- Crucially for enforcement, a registered user has the right to institute infringement proceedings in their own name (making the proprietor a defendant), subject to any agreement between the parties (Sec 52).39 However, Section 53 explicitly states that a person whose use is permitted but who is not registered as a user has no right to institute infringement proceedings.39

- The rights conferred on a registered user are personal and cannot be assigned or transmitted (Sec 54).39

The detailed “registered user” provisions represent a specific national implementation choice for managing trademark licensing within the Indian legal framework. While TRIPS Article 19 requires recognition of use by controlled persons and Article 21 allows national conditions on licensing 21, India’s formal registration system provides significant statutory clarity. It formally links the licensee’s use to the maintenance of the proprietor’s rights (Sec 48(2)) and explicitly grants registered licensees standing to sue for infringement (Sec 52), a right denied to unregistered licensees (Sec 53).39 This contrasts with jurisdictions that rely primarily on the terms of the license agreement and general principles of control to determine the effects of licensing. The Indian system thus offers a more structured and predictable framework for both proprietors and licensees regarding the legal consequences of permitted use, particularly concerning validity and enforcement rights.

F. Protection of Well-Known Marks (Sec 2(1)(zg), 11)

The Act provides robust and detailed protection for well-known trademarks, reflecting international trends and TRIPS requirements.

- Definition (Sec 2(1)(zg)): A “well-known trade mark” is defined in relation to goods or services as a mark that has become so recognizable to a substantial segment of the public using those goods or services that its use in relation to other goods or services would likely be taken as indicating a connection in the course of trade with the proprietor of the mark.38

- Protection Scope (Sec 11):

- Section 11(1) establishes that conflict with an earlier well-known mark is a relative ground for refusing registration of an identical or similar mark for similar goods or services if it causes a likelihood of confusion.33

- Significantly, Section 11(2) provides broader protection, mirroring TRIPS Article 16.3. It prohibits registration of a mark identical or similar to an earlier well-known trademark even for goods or services which are not similar, if the earlier mark is well-known in India and the use of the later mark without due cause would take unfair advantage of, or be detrimental to, the distinctive character or repute of the well-known mark.36 This protection against dilution or free-riding is reinforced by the corresponding infringement provision in Section 29(4).38

- Determination Factors (Sec 11(6), 11(7)): The Act mandates that the Registrar shall, when determining if a mark is well-known, consider a comprehensive list of factors.38 These include:

- Knowledge or recognition in the relevant public section (including via promotion).

- Duration, extent, and geographical area of use.

- Duration, extent, and geographical area of promotion (advertising, publicity, fairs, exhibitions).

- Duration and geographical area of registrations or applications reflecting use/recognition.

- The record of successful enforcement, including recognition as well-known by courts or the Registrar.

- Factors relevant to assessing knowledge in the relevant public include the number of actual/potential consumers, persons in distribution channels, and business circles dealing with the goods/services.38

- Key Clarifications (Sec 11(8), 11(9)):

- If a mark has been determined as well-known by any court or the Registrar in India, the Registrar shall consider it well-known for registration purposes (Sec 11(8)).38

- Crucially, Section 11(9) explicitly states that the Registrar shall not require, as a condition for determining well-known status, that the mark has been used in India, registered in India, applied for in India, or is well-known/registered/applied for in another jurisdiction.38 This directly addresses the principle of transborder reputation.

- Enforcement Obligation (Sec 11(10)): The Registrar is obligated, during registration and opposition proceedings, to protect well-known marks against identical or similar marks and must consider any bad faith involved.38

The level of detail provided in Section 11(6)-(9) for determining well-known status, particularly the explicit instruction in Section 11(9) that local use or registration is not a prerequisite, positions India’s statutory framework as exceptionally clear and potentially highly protective of famous marks.38 By expressly codifying the factors to be considered and rejecting territorial limitations as mandatory conditions, the Act provides strong support for claims based on reputation established among the relevant Indian public, regardless of whether the mark is used or registered locally. This goes beyond the general principles articulated in TRIPS Article 16 25 and reflects a deliberate legislative choice to offer robust, clearly defined protection for well-known marks, potentially influenced by evolving international jurisprudence and best practices concerning transborder reputation.

G. Enforcement Mechanisms (Civil – Sec 135, Criminal – Ch XII, Border Measures)

India has established a multi-pronged system for enforcing trademark rights, encompassing civil, criminal, and administrative (border) measures, consistent with TRIPS Part III obligations.

- Civil Remedies (Sec 134, 135):

- Reliefs: Section 135(1) outlines the reliefs available in suits for infringement or passing off. These include injunctions (subject to court terms), and, at the plaintiff’s option, either damages or an account of profits. An order for the delivery-up of infringing labels and marks for destruction or erasure may also be granted.40

- Interlocutory Orders: Section 135(2) empowers courts to grant ex parte injunctions or interlocutory orders for discovery of documents, preservation of infringing goods or evidence, and restraining the defendant from disposing of assets (akin to Anton Piller and Mareva injunctions).40

- Jurisdiction: Section 134 provides a convenient forum for plaintiffs. Suits can be instituted in the District Court having jurisdiction, or in a High Court exercising original jurisdiction, where the person instituting the suit (plaintiff/proprietor) actually and voluntarily resides or carries on business or personally works for gain, irrespective of the defendant’s location or where the cause of action arose.50 This overrides contrary provisions in the Code of Civil Procedure.

- Limitation: The limitation period for filing an infringement suit is generally three years from the date the cause of action arises.50

- Criminal Remedies (Chapter XII, Sec 101-121):

- Offences: The Act criminalizes various acts, including falsifying a trademark, falsely applying a trademark to goods/services (Sec 102, 103), making or possessing instruments for falsification (Sec 103), applying false trade descriptions (Sec 103), selling or possessing for sale goods/services bearing false trademarks or descriptions (Sec 104), and falsely representing a trademark as registered (Sec 107).39

- Penalties: Penalties for key offences like falsification, false application, and selling infringing goods (Sec 103, 104) include imprisonment for a term not less than six months, extendable up to three years, and a fine not less than fifty thousand rupees, extendable up to two lakh rupees.14 Enhanced penalties apply for second and subsequent convictions (Sec 105), with imprisonment not less than one year (up to three years) and a fine not less than one lakh rupees (up to two lakh rupees).39 Courts retain discretion to impose lesser sentences for adequate and special reasons recorded in writing.39

- Enforcement Powers: Crucially, offences under Sections 103, 104, and 105 are cognizable, meaning police can investigate and arrest without a warrant (Sec 115(3)).14 Furthermore, a police officer (not below the rank of Deputy Superintendent of Police or equivalent) can search and seize infringing goods, dies, blocks, machines, etc., without a warrant, provided they first obtain the opinion of the Registrar of Trade Marks on the facts and abide by it (Sec 115(4)).39 Courts can also order the forfeiture of seized infringing goods (Sec 111).39

- Border Measures (Customs Act, 1962 & Intellectual Property Rights (Imported Goods) Enforcement Rules, 2007):

- Legal Framework: Section 11 of the Customs Act, 1962, empowers the Central Government to prohibit the import or export of goods for specified purposes, including the protection of patents, trademarks, and copyrights (Sec 11(2)(n)) and the prevention of contravention of any law (Sec 11(2)(u)).11

- IPR Enforcement Rules, 2007: To implement TRIPS border measure obligations (Art 51-60), India notified the Intellectual Property Rights (Imported Goods) Enforcement Rules, 2007 (hereinafter “IPR Rules”) under the Customs Act.10 These rules apply not only to trademarks and copyrights (as mandated by TRIPS) but also extend to patents, designs, and geographical indications.10

- Procedure: A right holder can file a notice with the Commissioner of Customs, providing details of their registered IP right, information differentiating genuine and suspect goods, and furnishing a bond and indemnity to protect customs authorities and the importer against wrongful detention.30 An online portal facilitates this process.56 Upon satisfaction, Customs registers the notice, typically valid for at least one year, and issues a Unique Permanent Registration Number (UPRN).56 Once registered, the import of goods infringing the recorded right is deemed prohibited under Section 11 of the Customs Act.11

- Suspension and Action: Based on a registered notice or even suo motu in specified circumstances, Customs authorities can suspend the clearance of imported goods suspected of infringing IP rights.30 The importer and the right holder are notified. The right holder must then join the proceedings and provide further security within a short timeframe (e.g., 3 days).30 After examination, if the goods are determined to be infringing, they are liable for confiscation under Section 111 of the Customs Act and subsequent destruction.54 The rules exempt de minimis imports, such as goods in personal baggage or small consignments intended for personal use.30

India’s comprehensive enforcement framework, combining civil, criminal, and border measures, demonstrates a robust approach to implementing the obligations outlined in TRIPS Part III.21 The specific procedures established under the IPR Rules 2007 provide a clear administrative pathway for right holders to leverage customs authorities in combating imports of infringing goods, directly translating the principles of TRIPS Articles 51-60 into national practice.10 Furthermore, the designation of key trademark offences as cognizable, coupled with police powers of search and seizure (Sec 115), provides a significant deterrent, particularly against commercial-scale counterfeiting, aligning with the spirit of TRIPS Article 61.39 This multi-layered system aims to provide practical, accessible, and deterrent remedies against trademark infringement in its various forms.

IV. Comparative Analysis: Indian Act vs. TRIPS Requirements

A direct comparison reveals a strong alignment between the Indian Trade Marks Act, 1999, and the TRIPS Agreement, with the Indian legislation often providing more detailed provisions and, in some areas, exceeding the minimum standards set by the international agreement.

Comparative Table of Key Trademark Provisions

| Feature | TRIPS Provision (Art. & Summary) | Indian Act Provision (Sec. & Summary) | Compliance/Comparison Note |

| Protectable Subject Matter | Art. 15: Any sign capable of distinguishing; examples include words, letters, numerals, figurative elements, colour combinations. Acquired distinctiveness allowed. | Sec. 2(zb), 2(m): Mark capable of graphic representation & distinguishing; explicitly includes shapes, packaging, colour combinations, service marks. Acquired distinctiveness overcomes refusal (Proviso to Sec 9). | Compliant. India provides greater statutory detail and explicit inclusion of non-traditional marks. |

| Rights Conferred (Standard) | Art. 16.1: Exclusive right to prevent confusing use of identical/similar marks on identical/similar goods/services. Presumption of confusion for identical/identical. | Sec. 28: Exclusive right to use for registered goods/services. Sec. 29(1)-(3): Prevents use of identical/deceptively similar marks on identical/similar goods/services causing likelihood of confusion. Presumption for identical/identical. | Compliant. India’s Sec 29 provides more detailed infringement scenarios (see below). |

| Rights Conferred (Well-Known Marks) | Art. 16.3: Protection extended to dissimilar goods/services if use indicates connection and damages owner’s interests. | Sec. 11(2), 29(4): Prohibits registration/use on dissimilar goods/services if takes unfair advantage or is detrimental to well-known mark’s repute/distinctiveness. | Compliant. India uses slightly different language potentially encompassing dilution. |

| Minimum Term / Renewal | Art. 18: Min. 7 years initial/renewal term. Renewable indefinitely. | Sec. 25: 10 years initial/renewal term. Renewable indefinitely. | Exceeds Minimum Standard. Aligns with common international practice. |

| Exceptions | Art. 17: Limited exceptions (e.g., fair use of descriptive terms) allowed, considering legitimate interests of owner and third parties. | Sec. 30, 35, 36: Detailed statutory exceptions (bona fide description, own name use, lawfully acquired goods, use for accessories/parts, etc.). | Compliant. India provides more specific statutory examples of permissible exceptions. |

| Use Requirement (Filing) | Art. 15.3: Actual use cannot be a condition for filing. | Sec. 18(1): Application can be based on use or proposed use. | Compliant. |

| Use Requirement (Maintenance) | Art. 19: Cancellation possible after min. 3 years non-use. Use by controlled person recognized. | Sec. 47: Cancellation possible after 5 years continuous non-use from date of entry on register. Use by permitted user deemed use by proprietor (Sec 48(2)). | Compliant. India provides a longer (5-year) grace period. |

| Licensing | Art. 21: Members may determine conditions. Use under owner’s control recognized (Art 19). | Sec. 48-56: Detailed “Registered User” system. Permitted use by registered user deemed use by proprietor (Sec 48(2)). Registered user can sue (Sec 52). | Compliant. India uses a specific, formal national mechanism (registered user) providing statutory clarity. |

| Assignment | Art. 21: Permitted with or without goodwill. | Sec. 38, 39: Assignable with or without goodwill (registered & unregistered marks). Specific procedures for assignment w/o goodwill (Sec 42) and registration (Sec 45). | Compliant. India provides detailed procedural requirements. |

| Compulsory Licensing | Art. 21: Prohibited for trademarks. | Not permitted under the Act (implied by absence of provision and compliance with TRIPS). | Compliant. |

| Enforcement (Civil) | Art. 42-49: Fair procedures, evidence, injunctions, damages, other remedies, provisional measures (Art 50). | Sec. 134, 135: Jurisdiction provisions favouring plaintiff. Reliefs include injunction (incl. ex parte/interlocutory), damages or accounts of profit, delivery-up. | Compliant. India provides specific statutory reliefs and favourable jurisdiction rules. |

| Enforcement (Criminal) | Art. 61: Procedures/penalties for willful counterfeiting/piracy on commercial scale (deterrent fines/imprisonment, seizure/destruction). | Ch. XII (Sec 101-121): Specific offences (falsification, false application, selling), significant penalties (imprisonment & fines), cognizable offences, police search/seizure powers (Sec 115), forfeiture (Sec 111). | Compliant. India provides detailed offences, substantial penalties, and strong police powers. |

| Enforcement (Border Measures) | Art. 51-60: Procedures for customs suspension of suspected counterfeit trademark / pirated copyright goods upon right holder application (security, notice, etc.). | Customs Act 1962 (Sec 11) & IPR (Imported Goods) Enforcement Rules 2007: Detailed procedure for right holder notice, customs registration (UIPRN), suspension, examination, confiscation/destruction. Extends beyond TRIPS scope (patents, etc.). | Compliant. India provides a detailed administrative system (IPR Rules 2007) implementing and extending TRIPS border measures. |

The comparison highlights that while the Indian Act consistently meets the foundational requirements of TRIPS, it often elaborates significantly on the principles laid down in the Agreement. This is evident in the detailed definitions of infringement, the specific enumeration of exceptions, the structured approach to licensing via the registered user system, the comprehensive criteria for well-known marks, and the detailed codification of enforcement procedures and penalties. In areas like the term of protection and potentially the scope of well-known mark protection, the Indian Act appears to offer standards that exceed the TRIPS minimums.

V. Analysis of Compliance and Implementation

A. Adherence to TRIPS Minimum Standards

The Trade Marks Act, 1999, demonstrates comprehensive adherence to the minimum standards for trademark protection and enforcement mandated by the TRIPS Agreement. India, having been a signatory to the preceding GATT and subsequently the WTO Agreement, undertook the obligation to modify its domestic intellectual property laws to conform with TRIPS.12 The 1999 Act was the primary legislative vehicle for achieving this compliance in the field of trademarks, replacing the 1958 Act which predated the TRIPS framework.13

The analysis presented in Sections III and IV confirms that the core requirements of TRIPS Articles 15-21 and Part III find corresponding provisions within the Indian Act.

- The definition of a trademark and protectable subject matter in Section 2(zb) aligns with the broad scope envisaged in Article 15, including the allowance for acquired distinctiveness (Proviso to Sec 9).25

- The exclusive rights conferred by registration under Section 28, coupled with the detailed infringement provisions in Section 29, fulfill the requirements of Article 16.25

- The ten-year term of protection under Section 25 surpasses the seven-year minimum set by Article 18.25

- The statutory exceptions listed in Sections 30, 35, and 36 provide the limited exceptions permitted under Article 17, while respecting the legitimate interests involved.25

- The provisions regarding use requirements (Sec 18(1), 47, 48(2)) comply with Articles 15.3 and 19, allowing applications based on proposed use and setting a non-use period for cancellation (albeit longer than the TRIPS minimum).21

- The rules on assignment and licensing (Chapter V, Sec 48-56) adhere to Article 21, permitting assignment without goodwill and prohibiting compulsory licensing.21

- The protection afforded to well-known marks under Section 11, including the extension to dissimilar goods (Sec 11(2), 29(4)), implements the mandates of Articles 16.2 and 16.3.25

- The enforcement framework, encompassing civil remedies (Sec 135), criminal procedures and penalties (Chapter XII), and border measures (Customs Act and IPR Rules 2007), provides the effective mechanisms required by TRIPS Part III.10

India’s approach to compliance was not one of mere passive adoption or direct incorporation of TRIPS language. Instead, it involved a significant legislative undertaking to translate the international principles into detailed statutory provisions compatible with India’s existing legal system, which has strong common law roots.17 The resulting Act is a comprehensive statute that codifies trademark law extensively, integrating the TRIPS standards within a framework tailored to the national context. This demonstrates a deliberate effort to ensure not just formal compliance but also functional integration of international norms into domestic law.2

B. Provisions Beyond TRIPS Minimums (‘TRIPS-Plus’ Aspects)

In several areas, the Indian Trade Marks Act, 1999, incorporates provisions that offer protection or clarity beyond the minimum requirements stipulated by TRIPS. These elements suggest an ambition not merely to comply but to establish a modern and robust trademark regime aligned with contemporary international standards and addressing specific national priorities.

- Term of Protection: The ten-year term of registration and renewal (Sec 25) directly exceeds the seven-year minimum required by TRIPS Article 18.25 This longer term provides greater certainty and reduces administrative burden for trademark owners.

- Well-Known Marks Protection: While TRIPS mandates protection for well-known marks, including against use on dissimilar goods under certain conditions (Art 16.2, 16.3) 25, the Indian Act provides exceptionally detailed statutory criteria for determining well-known status (Sec 11(6)-(7)).38 Most notably, Section 11(9) explicitly prohibits the Registrar from conditioning well-known status on local use, registration, or application.38 This statutory embrace of transborder reputation, irrespective of territorial presence, offers potentially stronger and clearer protection than might be derived solely from interpreting the TRIPS text, positioning India’s framework as highly protective in this regard.

- Definition and Subject Matter: The explicit inclusion of service marks, shape of goods, packaging, and combination of colours in the statutory definition (Sec 2(zb), 2(z)) provides clear legislative backing for the protection of these non-traditional marks.14 While TRIPS Article 15 is broad enough to potentially cover such signs, the express statutory recognition in the Indian Act offers greater certainty.25

- Infringement Definition: As previously discussed, Section 29 provides a highly detailed account of infringing acts, specifically addressing scenarios like use as a trade name (Sec 29(5)), certain advertising practices (Sec 29(8)), and spoken use (Sec 29(9)).38 This level of specificity goes beyond the general “likelihood of confusion” standard in TRIPS Article 16, offering clearer grounds for action in various modern commercial contexts.25

- Enforcement Specificity: The detailed criminal penalties outlined in Chapter XII, including specific terms of imprisonment and fine amounts, and the cognizable nature of key offences with associated police powers (Sec 115), represent a specific national choice in implementing the general requirement for criminal procedures in TRIPS Article 61.21 Similarly, the comprehensive IPR Rules 2007 provide a detailed administrative mechanism for border enforcement that fleshes out the framework of TRIPS Articles 51-60 and extends its application beyond trademarks and copyright.30

These ‘TRIPS-plus’ features indicate that India utilized the TRIPS Agreement as a foundation upon which to build a more comprehensive and contemporary trademark law. The choices made reflect an engagement with international developments in trademark law (such as the increasing importance of non-traditional marks and robust protection for famous marks) and a pragmatic approach to addressing enforcement challenges within the Indian context through detailed statutory provisions and procedures. The Act thus represents not just minimum compliance but an effort to create a sophisticated national trademark system suitable for a globalizing economy.20

VI. Synthesis and Conclusion

Summary of Relationship and Compliance: The relationship between the trademark provisions of the TRIPS Agreement and the Indian Trade Marks Act, 1999, is one of foundational influence and comprehensive implementation. TRIPS provided the mandatory international framework and minimum standards, acting as a catalyst for India to overhaul its domestic trademark law. The 1999 Act demonstrates a high level of compliance with these TRIPS obligations, systematically incorporating the required principles regarding protectable subject matter, rights conferred, term of protection, exceptions, use requirements, transferability, and enforcement.2 The structure and substance of the Indian Act frequently mirror the requirements laid out in TRIPS Articles 15-21 and Part III.

Key Findings Recap: The comparative analysis reveals a strong congruence between the two legal instruments on core trademark principles. Both establish broad definitions of protectable marks, grant exclusive rights based on likelihood of confusion, permit limited exceptions, allow for assignment with or without goodwill, prohibit compulsory licensing, and mandate a tripartite enforcement system (civil, criminal, border). However, the Indian Act distinguishes itself through:

- Greater Statutory Detail: Providing more explicit definitions (including non-traditional marks), enumerating specific infringement scenarios, listing detailed exceptions, and codifying extensive criteria for well-known mark determination.

- Exceeding Minimum Standards: Offering a longer term of protection (10 vs. 7 years) and potentially broader protection for well-known marks due to explicit recognition of transborder reputation irrespective of local use/registration.

- Specific National Mechanisms: Implementing licensing through a formal “registered user” system and establishing highly detailed procedures for criminal and border enforcement (IPR Rules 2007, cognizable offences, police powers).

Concluding Remarks: The Trade Marks Act, 1999, successfully integrated India’s trademark regime into the international standards mandated by the TRIPS Agreement, contributing significantly to the global harmonization of intellectual property law. The Act provides a modern, comprehensive framework that not only meets but, in several aspects, exceeds the minimum requirements of TRIPS. It furnishes trademark owners with robust statutory rights and provides a detailed legal basis for their assertion. However, the practical effectiveness of this protection hinges critically on the consistent, efficient, and robust application of the enforcement mechanisms provided within the Act and related legislation.9 The availability of civil remedies through the courts, the prosecution of criminal offences, and the vigilance of customs authorities at the borders are essential components, as envisaged by both TRIPS and the Indian Act, to translate the legislative framework into meaningful protection against trademark infringement and counterfeiting in the marketplace. The 1999 Act provides the necessary legal tools; their effective deployment remains paramount.

Works cited

- All you need to know about the TRIPS Agreement – iPleaders, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://blog.ipleaders.in/all-you-need-to-know-about-the-trips-agreement/

- Analysing the Role of Copyright and Trademark in Business Transaction and India – ijrpr, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://ijrpr.com/uploads/V5ISSUE5/IJRPR28365.pdf

- TRIPS Agreement – Wikipedia, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TRIPS_Agreement

- Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights – USTR, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/wto-multilateral-affairs/-world-trade-organization/council-trade-related-aspects-in

- WIPO Lex, Treaties, Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement), accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/treaties/details/231

- Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) | Practical Law, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://content.next.westlaw.com/practical-law/document/I3a9a3477ef1211e28578f7ccc38dcbee/Agreement-on-Trade-Related-Aspects-of-Intellectual-Property-Rights-TRIPS?viewType=FullText&transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)

- Trade Policy – USPTO, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/ip-policy/trade-policy

- TRIPS Agreement of 1995 | All You Need To Know | Abounaja IP, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://abounaja.com/blog/trips-agreement-of-1995

- The Difference between WIPO and TRIPS | All You Need To Know – Intepat IP, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.intepat.com/blog/difference-between-wipo-and-trips/

- Anti-Counterfeiting Border Measures under Indian Customs Intellectual Property Rights (Imported Goods) Enforcement Rules, 2007 – Manupatra, accessed on April 30, 2025, http://docs.manupatra.in/newsline/articles/Upload/F913E1DB-0D15-4832-8A23-1B4BB14D37BE.pdf

- Chapter 21 – Intellectual Property Rights – Customs and Foreign Trade, accessed on April 30, 2025, http://www.customsandforeigntrade.com/CS%20chapter%2021.pdf

- Chapter 6 – India – WIPO, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo-pub-1079-chapter6-en-india-an-international-guide-to-patent-case-management-for-judges.pdf

- Trade Marks Act, 1999 | PDF | Trademark – Scribd, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/617363766/Trade-Marks-Act-1999

- PREFACE – IP India, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://ipindia.gov.in/writereaddata/images/pdf/proposed-tm-manual-for-comments.pdf

- Trade Marks Act, 1999 – High Court of Tripura, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://thc.nic.in/Central%20Governmental%20Acts/Trade%20Marks%20Act,%201999.pdf

- The Enforcement Of The Trademarks Act,1999: Challenges In The Indian Market, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-18327-the-enforcement-of-the-trademarks-act-1999-challenges-in-the-indian-market.html

- Indian trademark law – Wikipedia, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_trademark_law

- The Trade Marks Act, 1999 – iPleaders, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://blog.ipleaders.in/the-trade-marks-act-1999/

- Intellectual Property Act in India – Indian Institute of Millets Research, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.millets.res.in/books/chapter/Intellectual_Property_Act_in_India.pdf

- Designing a Global Intellectual Property System Responsive to Change: The WTO, WIPO, and Beyond (with R. Dreyfuss), accessed on April 30, 2025, https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3448&context=fac_schol

- TRIPS Agreement (Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) – WorldTradeLaw.net, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.worldtradelaw.net/document.php?id=uragreements/tripsagreement.pdf

- The Trademark Provisions in the TRIPS Agreement – Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1180&context=facsch_bk_contributions

- “The Trademark Provisions in the TRIPS Agreement” by Christine Farley, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_bk_contributions/99/

- TRADEMARKS A. General Part II, Section 2 of the TRIPS Agreement, that comprises Arts 15 to 21, concerns the protectio – Brill, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://brill.com/previewpdf/book/edcoll/9789004180659/Bej.9789004145672.i-910_020.xml

- Uruguay Round Agreement: TRIPS Trade-Related … – WIPO Lex, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/text/305907

- A Look at the Trademark Provisions in the TRIPS Agreement (Chapter 2) – The Cambridge Handbook of International and Comparative Trademark Law, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cambridge-handbook-of-international-and-comparative-trademark-law/look-at-the-trademark-provisions-in-the-trips-agreement/0E1CCBB4794B44093A1886611ECD2F6E

- Intellectual property, including the protection of trademarks under the TRIPS Agreement | WHO FCTC – WHO/OMS: Extranet Systems, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://extranet.who.int/fctcapps/fctcapps/fctc/kh/legalchallenges/intellectual-property-including-protection-trademarks-under-trips

- Plain Packaging and the Interpretation of the Trips Agreement – Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/context/vjtl/article/1270/viewcontent/Plain_Packaging_and_the_Interpretation.pdf

- Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights – Regulations.gov, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://downloads.regulations.gov/FDA-2012-P-0317-0001/attachment_38.pdf

- Intellectual Property Rights (Imported Goods) Enforcement Rules, 2007 – WIPO Lex, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/text/200427

- Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights with particular reference to the border – Blog | Sonisvision, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.sonisvision.in/blogs/enforcement-of-intellectual-property-rights-with-particular-reference-to-the-border

- WIPO/ACE/4/3: The Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights by Means of Criminal Sanctions: An Assessment, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/edocs/mdocs/enforcement/en/wipo_ace_4/wipo_ace_4_3.doc

- Trade Marks Act, 1999 – India Code, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/1993

- India Trademark Act and Rules – Invntree, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.invntree.com/resources/india-trademark-act-and-rules

- Title:: Indian Trade Mark Law and Compliance With TRIPS | PDF | Trademark – Scribd, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/460568756/IPR-final-draft-6th-SEm-docx

- Trademark Law in India – iPleaders, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://blog.ipleaders.in/trademark-law-in-india/

- Trade Marks Act, 1999 – WIPO Lex, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/text/128107

- TRADE MARKS ACT, 1999 – IP India, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://ipindia.gov.in/writereaddata/Portal/ev/TM-ACT-1999.html

- www.indiacode.nic.in, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/15427/1/the_trade_marks_act%2C_1999.pdf

- Remedies to Trademark Infringement – Asia IP, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://asiaiplaw.com/article/remedies-to-trademark-infringement

- Infringement Of Trademarks And Trade Names: A Comparative Approach To The Trademark Laws In India And European Union, accessed on April 30, 2025, http://annalsofrscb.ro/index.php/journal/article/download/7947/5877/14154

- Intellectual Property Rights, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.nacin.gov.in/ZCLucknow/Images/Documents/E_Exercises/10_IPR%20-%20Exercise-03.pdf

- The Trade Marks Act, 1999, India, WIPO Lex, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/legislation/details/22958

- Well Known Trademarks and Law in India – S.S. Rana & Co., accessed on April 30, 2025, https://ssrana.in/ip-laws/trademarks-in-india/well-known-trademarks-india/

- Civil & Criminal Remedies for Trademark Infringement – KAnalysis, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://kanalysis.com/civil-criminal-remedies-trademark-infringement/

- Trade Mark Law: Civil and Criminal Remedies Development Team – e-PG Pathshala, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://epgp.inflibnet.ac.in/epgpdata/uploads/epgp_content/S000020LA/P000846/M025744/ET/1513761526Q1e-textfinal.pdf

- Trademark Infringement and Remedies – Biswajit Sarkar Blog, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.biswajitsarkar.com/blog/trademark-infringement-and-remedies-in-india.html

- Section 135 in The Trade Marks Act, 1999 – Indian Kanoon, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/114856/

- Remedies available for Trademark Infringement – iPleaders, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://blog.ipleaders.in/remedies-available-for-trademark-infringement/

- A Comprehensive Guide to Understand Jurisdiction in Trademark Infringement Cases in India – Unimarks Legal Solutions, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://unimarkslegal.com/ip-news/trademark-infringement-cases-in-india/

- section 135 trade marks act 1999 | Indian Case Law – CaseMine, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/search/in/section%20135%20trade%20marks%20act%201999

- Trade mark litigation in India – Markshield, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://markshield.in/trade-mark-litigation-in-india/

- Enforcement of IPRs at Border :: Legal Provisions under Customs Act, 1962 – NACIN, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.nacin.gov.in/ZCLucknow/Images/Documents/E_Books/31_Enforcement%20of%20IPRs%20at%20Border%20Book%20No.03.pdf

- Bridging Borders: How Customs Laws Shape Trademark Protection in India, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.ipandlegalfilings.com/bridging-borders-how-customs-laws-shape-trademark-protection-in-india/

- Role Of Custom Seizures In Trademark Enforcement In India – KAnalysis, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://kanalysis.com/role-of-custom-seizures-in-trademark-enforcement-in-india/

- Protecting IP across Border through Customs – Obhan & Associates, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.obhanandassociates.com/blog/protecting-ip-across-border-through-customs/

- The Impact of TRIPS Agreement on International Trademark Regime, accessed on April 30, 2025, https://www.ijlmh.com/wp-content/uploads/The-Impact-of-TRIPS-Agreement-on-International-Trademark-Regime.pdf